I’ve blogged a lot about “transformation” of network operator business models, and also about transforming infrastructure. That’s an important issue to be sure, but there’s more to the cloud, network, and computing market than network operators. We know operators are responding to falling profit per bit. What’s driving the enterprises? Operators invest in IT and networks for cost reduction, more service revenues, or both. What do enterprises invest for? The answer, I believe, is clear. It’s productivity. That’s what I want to cover today.

What should we call the effort to improve business productivity via information technology? “Transformation” or “digitization”? Just the fact that we have to think of a name for the thing is a bad sign, because a name trivializes something that we’ve not really gotten around to defining. Say the name, and you identify the concept. Sure, but you don’t architect it, and that means that the fact that all real “transformations” are broad ecosystemic changes is lost in the hype shuffle.

What made the Internet transformational? The original Internet protocols, and even the original services of the Internet are totally unknown to the vast majority of Internet users. Was it the invention of the worldwide web? Sure, that was important, but suppose that all those consumers who jumped on the benefits of the web had nothing to get online with in the first place? So was it the Steve Jobs or the IBM PC that created the wave? I think the point is clear. The transformation happened because a lot of things were in place, not because one thing came about. We can’t pick one of those things and say it’s a revolution, or assess its market impact, without considering the sum of the ecosystemic parts.

This is why so many market forecasts are…well…crap. You can’t forecast the market for a piece of a suppositional ecosystem, and if you can’t make the suppositional ecosystem real you can’t even say what the pieces are or how they’d play in the final assembly. The good news is that while foresight may fail here, hindsight offers us some hope.

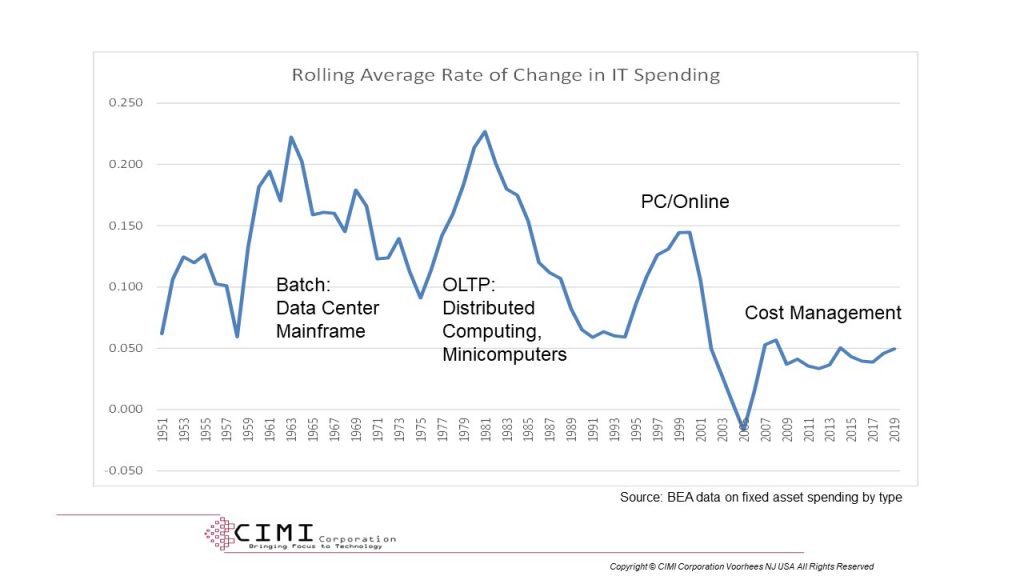

The chart above is a modern version of one I produced for the financial industry 15 years ago, based on data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. This version is the rate of change in core IT spending per year, based on a five-year moving average to reflect depreciation cycles. The chart shows clearly that there were three distinct periods when IT spending rose more than average. If we align industry technology events with the same timeline, we’d see that the first of these peaks coincided with the adoption of data center computing and batch processing, the second with the adoption of distributed minicomputers and online transaction processing, and the third with personal computing and online Internet information delivery.

I submit that each of these periods, periods when IT spending was above average, represented periods when the benefits associated with incremental IT spending were above average. Put another way, they represented times when a new paradigm for worker empowerment came on the scene, and companies exploited that by building out more infrastructure to gain the benefits. When they’d fully realized those benefits, spending fell back to normal patterns.

At the time of my first presentation of this data, I told audiences that unless the IT industry devised another empowerment paradigm, IT spending growth would stagnate. The modernized chart above shows that’s just what happened. During the period since 2005, companies saw the share of IT spending associated with “budget” maintenance of current applications grow, because the number of new productivity projects to inject new funding declined. No new benefits, no new spending.

In each of the periods of past productivity cycles, IT spending grew more rapidly than the average rate, a result of the injection of additional project budgets to drive spending overall. The rate at which spending grew (on the average, the growth rate tripled at the peak) seems related to the complexity of planning for and adopting technology to support the new paradigm, but in general it required only three or four years to reach peak. The declines in spending growth representing the maturing of the new technology, took longer than the peaking process did. It’s important to note that spending growth didn’t decline below norms (roughly a 5% rate per year) between cycles, which shows that once the equipment/software associated with a new paradigm was acquired, it added to the base of technology to be maintained through orderly modernization thereafter.

The chart suggests that if we were able to define another productivity investment cycle, we could triple IT spending growth, keeping it above average for about ten years. Is this almost a statistical validation of the “next big thing” theory? No, it’s a validation of the next big paradigm, a paradigm made up of many things, which individually might not be transformational at all. Even to describe the waves on my chart, I’ve been forced to trivialize the nature of the technology changes that led to each wave. Otherwise my legends wouldn’t fit on the chart. We need to get past the labels, even mine, to see some truths.

The truth, I think, is actually simple. This hasn’t been about computing or software or networks at all, but at getting information processing closer to the worker. Data centers in the first wave were doing batch processing of records for transactions already completed manually. In the second wave, we moved processing to the transactions themselves through online transaction processing (OLTP). In the third wave, we gave workers their own “data center” (even the first IBM PC had as much memory and processing power as a data center system in 1965). IT is migrating, approaching, and the vehicle is just a convenient set of tools that fit the mission.

So what’s the mission? I’ve used this term before; it’s point-of-activity empowerment. We need to get information not to the desk of the worker, but to the worker at the time and place where work is being done. That’s what the other waves did, and it worked. 5G isn’t the wave, nor is the cloud, nor mobile devices, nor IoT, augmented reality, robotics, or the other stuff often suggested. Those are just part of that “convenient set of tools”.

How, then, do we get things started on that wave, if what we need is a set of mutually interdependent pieces? What egg or chicken leads the charge to the future? What is the binding element of the ecosystem we’re trying to create. I think we know the answer to that, too, from chart-hindsight. It’s applications, and (of course, you know me!) application architectures.

What’s the difference between the hypothetical point-of-activity-empowerment wave and other waves? The answer is what IT is doing for the worker, which is also the difference from wave to wave overall. But in past waves, we had an advantage in that we could conceptualize the application from the first, and so we were simply doing the tool-fitting process iteratively as technology advanced. Processing an invoice in the mainframe age was reading a punched card with invoice information, prepared from actual paper invoices. In the OLTP age it was reading the data from a terminal as the transaction was occurring. In the PC/online era, the buyer entered the order and nature took its course from there.

There is no invoice in the next wave, because what we’re doing is, in a sense, getting inside the work process to deal with the job overall and not the final step in the job-process. What that requires, I think, we have to approach deductively, and I propose to do that by referencing something I’ve been calling “jobspace”. The “jobspace” for a worker is the sum of the information content of their job, from all sources including their own senses. Point-of-activity empowerment means projecting more/better information into worker jobspace, and presenting the contents of the jobspace better.

One obvious thing is that we need to have a portal to information in the hands of the worker, which means a smartphone or tablet with ubiquitous broadband connectivity. We have that now, but we’ll have to see whether what we have is enough by looking deeper.

The key element to point-of-activity empowerment is knowing what the worker is trying to do without having to force them to decompose their activities into steps and ask for the associated information. This has three components. First, knowledge of the environment in which the worker is moving. That would be a mission for location tracking (GPS) and IoT. Second, a knowledge of the assignment, meaning a goal or sequence that the worker’s job will necessarily involve. Finally, a means of presenting information to the worker contextually, meaning within the real-world and assignment context.

It’s long been my view that the broad benefit of IoT is to create a computer analogy of the real world, a parallel universe in a sense. This information has to be presented, not requested, or the process of empowerment will take up too much time. However, the idea that we can obtain this by reading sensors is silly. My suggestion was, and is, that sensor information, or any other kind of “real-world” information, be visualized as an information field. A worker moves through the real world, and intersects a number of information fields, from which information is “imported” into the jobspace, based on what’s needed.

The “what’s needed” piece is an important one because it defines the information content of the worker’s mission. Think of it as a pick list, an inventory of what conditions or information is required or to which the worker must be aware. If the worker is looking for a carton in a vast warehouse, they need running directions on getting to it, which means a combination of its location and their own. Point of activity empowerment demands not just that we define what we want the worker’s end result to be, but also what we expect the worker will have to do, and use, to get to that result.

The “information manifest” for this will have to be produced by line organizations using a tool to describe things. For those who have used UML for software architecture, my diddling suggests that it would be pretty easy to adapt UML to describe a job sequence and information manifest. However, the creation of this might well be an AI/ML application too. You can see, in particular, that having a worker go through something under ML observation, then having ML create the necessary descriptions, could be logical.

For the third element, contextual presentation, we have multiple options that are likely arrayed in one direction, which is augmented reality. In point-of-activity empowerment, the information channel has to combine the jobspace and the real world, which is what an AR device does. This isn’t to say that every point-of-activity empowerment project has to start with AR, only that we should presume that AR is the end-game and frame our application architecture around that presumption.

What’s important in the AR model is the recognition that the level of integration between the real world and the jobspace will depend on the specific visual pathway to the worker. Our visual sense is the only one rich enough to convey complex information, so we should assume that contextual analysis of worker position and information fields would provide us jobspace content. Displaying it depends on how capable the visual pathway is.

If the worker has a tablet or phone and nothing else to look at, then we can’t integrate things like what direction the worker is looking to determine what they want. In this case, we could presume that the worker could use voice commands or screen touches to convey their focus of attention. If we have an AR headset, then we need to link the jobspace elements of a given object in the real world, with the place that object takes in the worker’s visual field.

The key point here goes back to my comment on the “Internet transformation”. Suppose we had no PCs in place when Berners-Lee developed the web. Would the Internet have taken off? Or suppose we didn’t have the web, even though we had PCs. Or broadband to the home, without one or the other. Sure, there are things that might have happened to allow something less than the full ecosystem we had to develop into something, but it surely would have taken longer. The same will be true with our next wave of productivity, and it’s certainly possible that because we as a market seem incapable of deep thought, we won’t develop any new ecosystemic support for point-of-activity intelligence. What happens then? I don’t know. I have no idea what could create the next wave of productivity empowerment, if it’s not what I’ve described here. Perhaps other smarter people will have a notion; surely many will claim they do. I’m doubtful there is one, but you’re free to bet as you like.

Five good architects in four months could design all of this. It’s far from impossible, and my view is from the perspective of someone who spent years as a software architect. But to be “not impossible” isn’t the same as being automatic, and as long as we believe that all we have to do is mouth a marketing slogan and the technology it represents immediately becomes pervasive, we’re lost. There’s real work to be done here, and that’s the bad news. The good news is that I think that—eventually—somebody will do it.