How big is IoT? Obviously, it’s one of the most hyped of all technologies, with heady estimates of spending rampant and all manner of vague business propositions to back those estimates up. It turns out that it’s very difficult to estimate just what IoT’s impact would be, for a variety of reasons. I’ve undertaken a massive amount of modeling just to get some information on the US market, and also talked with a large number of enterprises who would theoretically be the ones spending that money. The results have been interesting, and frustrating.

If we consider IoT to be anything where a device communicates without a human pushing real or virtual keys, the global market in 2020 appears to have been about $800 billion. My model suggests that that total market will grow only about 8% in 2021, making it roughly $870 billion, and even in 2022, my model says that the number will barely top $900 billion. My model also says that most of the current IoT spending isn’t what would have been considered IoT at all under the logical definition that IoT means that you have a “thing” that is on the “Internet”. It’s largely in-home WiFi-based technology.

But IoT is, well, a highly diffused space. On the one hand, people who want to propose giant numbers and rates of adoption will include anything that communicates in the space. Consumer IoT, the household gadgets that connect to phones or to “assistant” applications, obviously represent a potentially enormous market, one that could easily hit a billion devices. However, these devices are assigned private subnet addresses in nearly every case, and their impact on Internet traffic and services is actually very limited. One consumer gadget technologist confided that their application, which involved some video exchange, used far less bandwidth in a month than an hour of streaming video used. A thermostat application would be a pimple on a single streaming show.

Consumer security applications are a bit of an IoT gray area. The majority of home security systems will use local wiring or short-range RF protocols like Zigbee, and they involve the “Internet” and literal IoT only insofar as they may provide for smartphone control, which almost always uses IP and often involves the Internet. In a sense, these applications are similar to smart thermostats in that their sensing and operation are separate, with the Internet involved in the latter but rarely in the former.

Smart buildings tend to differ from consumer IoT more in the way that information is integrated and used than in how it’s gathered. In fact, many smart buildings use residential-like technology up to a local controller, where the information is aggregated and where local actions are then supported. The Internet may be used to connect these local controllers back to an actual IT system, which might include providing for smartphone control and notifications.

Industrial IoT, which is the largest segment of the IoT space outside the consumer, is more like what we’d think of as “classical” IoT. Even IIoT, to use the popular term, is similar in many ways to smart-building systems. There are sensors, usually connected through wiring or a specialty RF protocol, and messages are passed from them to a local controller that will often generate local responses to control elements, keeping latency low and eliminating the risk of a communications failure creating havoc. From that local controller, data is often then passed on to a corporate information system where several applications may be involved.

The original notion of IoT, which was a rich set of public sensors that, like the Internet, could be exploited by third-party OTT-like players, has never emerged for obvious profit, security, and privacy reasons. What might replace that, at least for some missions, are the set of IoT services that would be related to a totally different set of new services, ones I’ve called contextual services, but that I’ll generalize to “visionary IoT” here. Some of this visionary IoT could be deployed by enterprises, and some might be deployed by network operators, cloud providers, or even governments at some level, in order to create a broad set of new applications for both businesses and consumers.

While IoT advocates who want to propose large markets tend to lump all these categories together, those who want to propose significant impacts, significant changes to how we live and work, will either cherry-pick segments of the total market and generalize them, or simply make vague statements about impact without linking them to anything in particular. This makes it very difficult to size the IoT market or predict IoT spending, and I’ve worked since early in 2021 to try to come up with something useful. Here’s what I’ve decided.

The potential for significant impact from IoT aligns primarily with what I’ve called “contextual services”, which means that the largest value of IoT lies in its ability to reflect conditions and actions between the real world and a digital twin or virtual-reality parallel. The problem is that visionary IoT services involve a lot more than just IoT, and there is little or no awareness of the broad concepts or what’s inside it. That means that it’s extremely difficult to model a market scenario with any credibility, unless you make assumptions.

The first critical assumption is that our visionary version of IoT will not create a universe of public sensors, but will instead be based on services created from sensors deployed by companies who plan to profit from their sales. The most likely model for these services is the one used by public cloud providers to offer cloud-resident “web services” that developers build on.

The second critical assumption is that visionary IoT will demand support from other applications that can convey “mission context”. IoT can tell us a lot, but it’s not enough to uncover why we’re doing what we’re doing, or even what our specific purpose might be. Traveling along (walking or riding) is something that IoT could likely detect, and it could perhaps extrapolate our destination based on path and past behavior. If we could tie in the fact that we had a reservation at a restaurant in the direction we’re heading, and that we had just had a conversation with someone we often dined with, IoT could offer a much better sense of what we were trying to do, and offer us more useful guidance.

The final critical assumption is that visionary IoT will pass through a traditional tech investment adoption curve, one that rises to a peak then falls back to a maintenance level. This is how past IT investment cycles have progressed, and there’s no reason to think that IoT would be any different. With this assumption, it’s possible to judge the market impact by knowing roughly when the transformation will start and how high the peak will go.

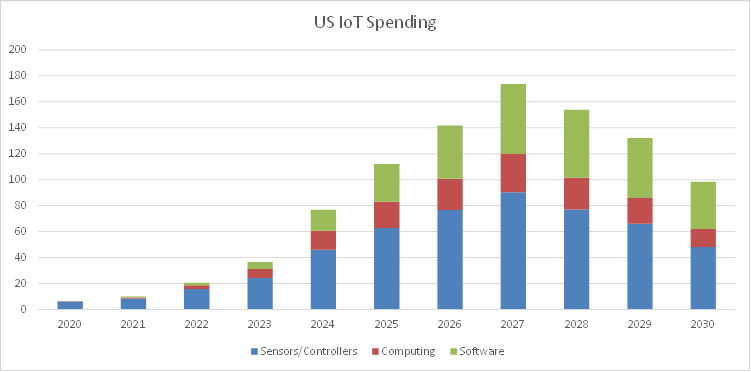

The figure above shows the result of my modeling. According to my model, the visionary form of IoT we’ve been expecting (or at least hoping for) emerges in three phases. First (through this year), there’s early deployment of IoT equipment (sensors and local controllers) that prep for a more visionary use of the technology. In 2022 and 2023, this results in a deployment of computing services and equipment, and then of software, that exploit those deployments. This starts to reduce the portion of visionary IoT spending that relates purely to IoT elements, and it reflects the period when the architectural model for visionary IoT emerges, the model that will drive the cycle’s growth. I think it’s likely that cloud providers will create this model and it will tie local IoT processing into the public cloud.

The year 2025 represents the real start of the IoT cycle, with a significant increase in total visionary IoT investment as the architectural model takes hold. The cycle peaks in 2027, and then slowly declines through 2030, which is the limit of the model to project. IoT element spending is stable as a percentage of total spending from 2028, and software gains slightly while hosting declines slightly through the end of the model. This is because the market, at this point, is driven by expanded use of contextual applications, largely a matter of software.

The model also shows other shifts, in the “who” and the “how”. As we advance to 2024, we see first a period where visionary IoT is more focused on per-company strategies, and then (in 2024) a shift to a more ecosystemic model. This shift drives a significant increase in IoT software spending, associated with creating a broader model of how IoT data is used and shared (I’ve called this the “information field” approach in prior blogs). From just past the midpoint of 2024, this broader IoT model is what’s driving the market.

Another shift related to this one is the shift from premises-focused IoT hosting to cloud-and-edge-focused. This really starts in 2023 according to my model, and is based on cloud-provider improvements to their “private edge” strategy. By 2026, though, we’re seeing the majority of hosting growth coming from adopting true edge computing as a service, and that strategy dominates by the peak in 2027.

A couple of closing points are appropriate here. First, while I’m pleased with how my model has worked, no model is perfect, and in this case in particular there are so many variables and constraints involved that I can’t say I’m happy with the outcome. I’ve had to create constraining assumptions to prevent the model from “oscillating”, meaning showing wild and unrealistic swings, and that means that the constraints I’ve cited here have influenced the outcome. Until we have a clear market direction that will set its own constraints, this is unavoidable unless I don’t want to model at all. Second, the model suggests that the range of possible outcomes varies from about 12% of the numbers in the figure to almost five times those numbers, even within the constraints I’ve applied. That reflects the fact that even with constraints, there are questions about who and what drives the space, and answering these in a different way could have a major impact on the results. Visionary IoT could indeed be a revolution, or it could be a total dud.

What I do hope the exercise here could do is identify the things we have to validate about visionary IoT (my constraints) and identify critical parts of the evolution to success (the phase points I call out above) that need to be somehow supported with market initiatives. It’s likely to be how well, and how quickly, we can accomplish these things that will determine how impactful visionary IoT will be.

Finally, remember that I’m not trying to forecast everything that advocates want to call “IoT”; there are no boundaries to that. This is “visionary IoT”, the kind that involves the creation of some sort of IoT ecosystem that can be broadly exploited without risks to privacy, security, or public policy. I will revisit these numbers from time to time if conditions change.